Gardening

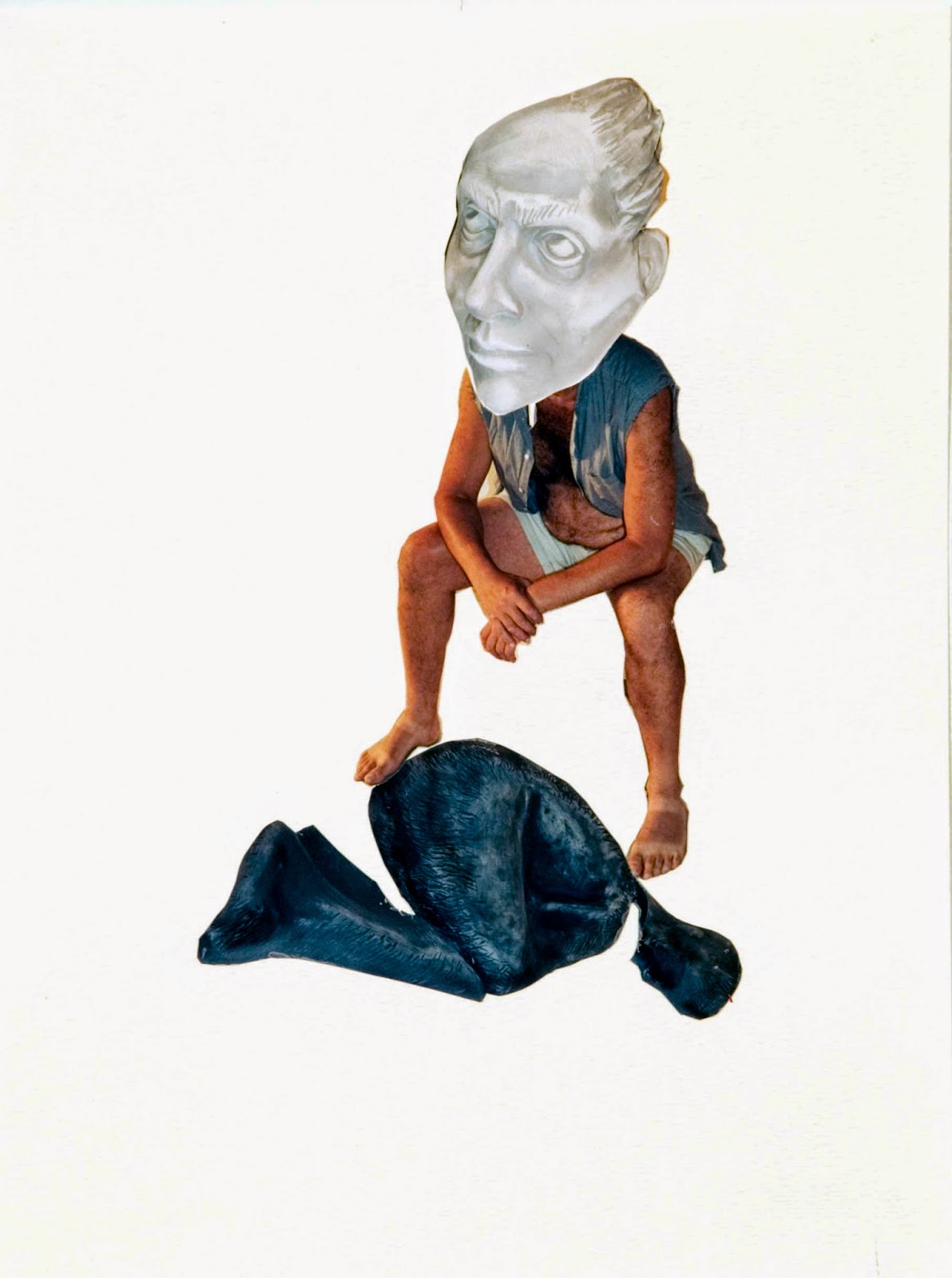

photo collage

Elections have become stressful times to which I do not look forward.

2015 approaches, however, and I’m afraid it will be yet another campaign with a

‘lesser of evils’ outcome, especially for those of us in the Arts.

I had a thought as Canadian politicians

begin their pre-federal-election campaigns. Maybe there could be a requirement that

people wishing to put their names forward as candidates first complete a rigorous degree on Leadership, regardless of their political parties.

Oh, I know many people disdain

education, and higher education especially.. They’ve made it without Masters or

PhDs to influential positions by sheer will, arrogance, and canniness. I think that’s not because education is

over-valued, but because of individual personalities. We all admire people with

drive, ambition and self-confidence, and they, whether they have degrees or

not, rise to the top.

Problem is,I think that a community, no matter its

scope, is not really defined by its elite, its business, its military or its

competitiveness. These things are the direct result of its Culture: they are a

result of the Values that define it and the way it applies these as it relates

to other communities. A community, especially when it is ‘A Nation”, is an

extremely complex and nuanced entity, even in dictatorships, even when they

grow out of terrorism or colonialism. This is true especially in a country that

functions democratically, especially in a country like Canada that prides

itself on its multiculturalism, its social safety network and its sober, fair

approach to international relations. Any Canadian leadership candidate should

have to prove she or he is up to leading the community from these core Values.

In Canada, the Leadership degree could

be offered by existing universities but evaluated by an independent body. Representatives

would come from all regions of the country. For regional-level leaders, for

instance, each region would select its best thinkers in public, private, military

and corporate sectors, male and female, to create the curriculum, including rigorous

Human Rights and Heritage sections. For national level contenders, top thinkers

the world over would design and add courses to cover World Cultures, Global

Environment and International Human Rights, for instance. The course creators

would determine the grading, standing structure and examinations, select the

educators (for limited, rotating contracts) and award the Leadership degrees.

For these degrees, a balanced number of men and women would have to enrol.

Courses would cover the major areas

of public concern: men’s, women’s, children’s, seniors’ and family rights

(regardless of religion or orientation), Aboriginal rights, military rights,

animal rights and health, human health, environmental health, education,

culture, multiculturalism, visual and performing arts, sports, competition,

infrastructure, economy, budget, international affairs, technical and

scientific research and development, banks, etc. A scoring system could be

determined, and a minimum total score required for the person to earn the right

to be a ‘Leadership Candidate’.

Once so prepared, and only then, the

graduates would be eligible to run for office. They would each be expected to conduct

themselves like leaders: no more talking down to or disdaining voters, no more

gratuitous attacks on their opponents, no more focus simply on charisma or

personality. And no more promises without a clear, concrete explanation of how

they would honour these promises: perhaps their platforms could be drafted as

legal contracts?

Why a degree? Why not just business

acumen or a camera-friendly face or a strong lobby group and an ‘après moi le

deluge’ attitude (Oh, Steven!)? Because somewhere somehow, prospective

politicians need to understand that leadership is not the same as ownership.

They need to be more than the sum of their own interests. Making them become

learners might help to broaden their thinking, un-blinker their eyes, re-direct

their attention and make their candidacy about broad-based ideas and achievement, not power grabbing or partisanship.

Maybe really good people are

hesitant to run for office because they don’t feel qualified, leaving it to

‘career politicians’ to focus on keeping their jobs rather than on leading.

Maybe they’ve lost faith in the electoral system, which seems to have been

tampered with to serve… whom? Too many candidates grasp for

power by any means during elections and then forget they are elected and not

divinely appointed, protected by their term of office and rewarded for their

‘service’ no matter what its quality with a nice, for-life pension at the end.

Perhaps what I propose would be

complicated. Perhaps it would take a huge amount of effort, cooperation and be

costly. Perhaps it would affect everyone’s behaviour. Perhaps it would require

the involvement of more citizens than currently turn out to vote. Perhaps it wouldn’t solve

all leadership problems in the world, for, as far as I can see, they are huge.

Maybe it would be worth the trouble.